During the game against the USA, the Colombian defender Andrés Escobar, who was about to move to AC Milan, made an own goal, which caused his death.

In modern football, there is a lot of discussion about the very high levels of stress that professional players are subjected to. Yet in 1994, during the World Cup in the United States, the 22 players of the Colombian national team, were under much greater pressure than you can imagine.

Colombia is only now recovering from a long conflict over the cocaine trade. At the beginning of the 1994 World Cup, Pablo Escobar -- the most famous narco-trafficker ever, allegedly responsible for the deaths of over 500 soldiers, thousands of criminals as well as several judges, politicians and at least one soccer referee -- was already dead by six months, but the war between the government and the narco-traffickers continued relentlessly in the chaos generated by his disappearance.

So much money was being spent among the drug traffickers that it was obvious that they would have an influence on the world championship too, even though no one expected repercussions as brutal as those that the world had to see that summer.

Andrés Escobar was, first and foremost, an athlete. It would, therefore, be unfair to talk about his death without first analyzing the context in which he finds himself, even only in order to clarify the extraordinary opportunities that the Colombian team would have had if it had not been paralyzed by fear.

Of the 26 games that preceded the World Cup, Colombia lost only one. During the entire qualifying phase the team only conceded two goals and qualified by beating the Argentina of Fernando Redondo, Diego Simeone, and Gabriel Batistuta 5-0 in Buenos Aires - a result celebrated by the highest recognition in the world of football, that is a standing ovation received by the opposing fans. Colombia was certainly not short of champions: just think of Freddy Rincón, Carlos Valderrama, and Faustino Asprilla. It was this team of big names that introduced themselves to the 1994 World Championship under the leadership of Andrés Escobar.

"Maintaining concentration is not easy, but I try to get the motivation from the good things that are waiting for us," said Escobar, 27 years old, before the start of the games, in view of his move to Italy where he was supposed to play for AC Milan. "I try to read passages from the Bible every day. My bookmarks are two photographs, one of my dear mother who is no longer there and the other of my girlfriend." Friends and relatives portray Andrés as a man who really believed that football could save Colombia.

A point of view also shared by Michael Zimbalist, who along with his brother Jeff directed "The Two Escobars", a documentary that tells the story of those two men who share the same name but are extremely distant from each other, and whose lives have met to show to the world the true soul of the Colombian society.

"Today Colombians are seen as bad people around the world," explained Zimbalist. "The Colombian national team of the time, led by Andrés, was trying to erase this negative image, although I believe that in reality it still persists today, not only in the world of football but for all Colombian citizens. Personally, I have never met anyone so determined to change the perception of the country in the eyes of the world.

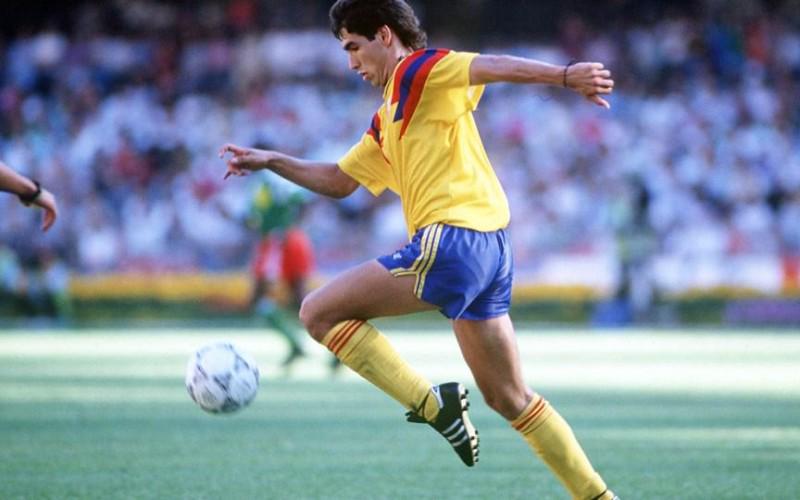

Part of these prejudices also derive from what happened when in 1994 Colombia played against the United States in the second group stage game. They had already lost 3 to 1 against a Romania surprisingly in form-principally thanks to Gheorghe Hagi, who before the internet era shared the performance of each player on the face of the earth, managed to win the attention of the media by whizzing on televisions around the world like a lightning bolt in clear skies. In that opening match, Hagi scored one of the most memorable goals of the competition, an amazing goal that caught the Colombian goalkeeper Oscar Cordoba by surprise. Thanks to the extraordinary performance of the Romanian goalkeeper and perhaps because of the tension in the Colombian team was the Hagi team to win the match, turning the next game with the United States in the match that Escobar and associates could not really afford to lose.

Looking at those images today it's hard not to wonder what was inside Escobar's head when, at the 34th of the first half, he deflected the cross of the American midfielder John Harkes into his own goal and became an own goal. Could it be that he had not realized the implications that this fatal error would have on his life? Apparently his nine-year-old niece, who was watching the match from home in Medellín, already had everything clear. "At that moment he told me 'Mom, they'll kill Andrés,' the Colombian defender's sister told me in an interview for The Two Escobars. "I answered him, 'No baby, no one is killed because he made mistake. In Colombia everyone loves Andrés.

Needless to say, the team tried everything after that goal, but nothing seemed to go right up to the 90th minute when Adolfo Valencia managed to put the ball into the net. At that point, however, the team was already at a two-goal disadvantage and there was no way to save the situation. The Colombians had lost again and were preparing to return home, after a valorous but in vain 2-0 against Switzerland in the last game of the round.

In a way, home was the last place where players would like to return. In fact, it was as if they had never managed to escape. The defeat against Romania had infuriated so many people, not only for sporting reasons but especially for the money they gambled on the Colombian victory. When the players returned to the hotel after the defeat, the TV screens were manipulated and instead of the traditional welcome messages, they broadcast terrible threats and insults. Defender Luis Herrera discovered at that time that his brother had died in a car accident and Colombian coach Pacho Maturana was warned harshly: if in the following match the midfielder Gabriel Gomez had played, all the other players would have been killed.

It was in this environment of tension and terror that Colombia faced the second game of the round against the United States. "Psychologically we were under tremendous pressure. At the time, when we were talking about murderers were not just empty threats," explained Zimbalist. "People were dying at absurd rates in Colombia. You can imagine how difficult it is to give the best on the field when your family's life is at risk.

Most people wouldn't even be able to cook an egg if they knew that their family's life was at stake, not to mention trying to win the World Cup. Despite everything, once home, Andrés continued his battle for peace in the country, without being influenced by the elimination from the World Cup. He decided to write an open letter in the daily newspaper of Bogota, El Tiempe, where he asked the country to unite against violence and anger. "Life doesn't end there. We have to move forward... Even if it can be difficult, we have to get up," he wrote.

Ten days after the fatal own goal in the match against the United States, Andrés decides to go out for the first time, to drink something with friends, at the bar El Indio of Medellín. Although Herrera and Maturana had advised him not to go out.

At a certain point of the evening, four men follow Andrés out of the club and in the parking lot they beat him up and call him "gay boy". The captain, upset, tries to explain himself, repeating that it was not his intention at all, asking them to understand. Six bullets later, Andrés will sink into the passenger seat of his car. The intervention of the ambulance to try to revive him will be in vain.

"Obviously we were aware of what had happened," says Terry Phelan, in the ranks of the Irish team at the World Cup. "Kill for an own goal, do you really need someone to lose his life for it? I remember talking about it a couple of years ago with Carlos Valderrama, who cried when I appointed Andrés. He told me it was still too painful for him. And so you ask yourself, 'Why?

It is a legitimate question, and at the same time a question that has no answer and perhaps never will. The thesis that took hold at the time, was that the murder had been caused by the large sums of money lost in betting. Many people still think this is true today. However, eyewitnesses told the police that the vehicle in which the culprits left that night was owned by Pedro and Juan Gallón, two narco-trafficking brothers who operated on behalf of Pablo Escobar, before moving on to the rival Los Pepes sign. At the time, however, the Gallón brothers came out clean, because one of their bodyguards-Humberto Castro Muñoz-confessed the murder and served 11 years, on a sentence of 43 years.

However, one of Pablo Escobar's assassins, Jhon Jairo Velásquez Vásquez-o "Popeye", repentant and now famous youtuber in his homeland, has always claimed that the Gallón brothers corrupted the right people, paying up to three million dollars to get out of it unscathed and get Muñoz locked up. Vásquez also argues that the reason for the murder was not money lost in betting. "Andrés' mistake was to respond to those geeks," he said in one of several interviews. "The Gallón brothers' ego was so swollen after they killed Pablo that they would never allow anyone to respond, not even Andrés. The bets had nothing to do with it, it was a fight that ended badly, that's all.

If between accusations and counter-attacks between drug killers and the questionable reliability of the Colombian judiciary system it is rather difficult to shed light on those who pull the trigger on that summer night in the mid-nineties, perhaps, in a sense, it does not even have much importance. Strange as it may seem, for the role Andrés played and for his approach to the society of the time, perhaps the condemnation of his murderer to prison would not be enough to avenge his death. His only wish would have been to see an end to the violence and murders in his country and to see the people he loved free from the oppression of civil war.

"We started with the idea of making a film about who killed Andrés Escobar, but in the end we found ourselves with a broader cross-section of Colombian society as a whole - I think Andrés's life, as well as his death, is linked to the history of the country; it goes far beyond the simple question of who pulled the trigger," explained Zimbalist . "Andrés was an example of hope in the darkest moments, and it is precisely for this reason that his death shocked the whole country in the depths. I don't think there will ever be an 'emotional' conclusion to his murder, it was a real shock to his family, his teammates, his friends and the whole country. Finding the name of the murderer could only partially solve his case, but the real resolution of the Andrés and Colombian affair will be to see the country flourish and grow in a positive direction.

Source: Vice.com

Comments