Gymnastics recently had 178 people on its list. Swimming had 163. Another 31 are on the list from taekwondo, 29 from figure skating and 33 more from judo.

The lists reflect the hundreds of people who have been barred, often for sexual misconduct, from the federations running these sports as well as others overseeing the development of Olympic athletes. A few of the names are well known, perhaps none more than Larry Nassar, the former team doctor for USA Gymnastics who was sent to prison after being accused of sexually abusing scores of young female athletes.

Yet, the sheer scope of the lists, and the inconsistencies within them because of differing standards among the organisations, raise plenty of questions — not the least of which is whether an effort to collect and publish the names is even legal, given that, until recently, people were disciplined by the governing bodies, each with its own brand of justice. There are also questions about transparency and whether individual sports are divulging all past offenders.

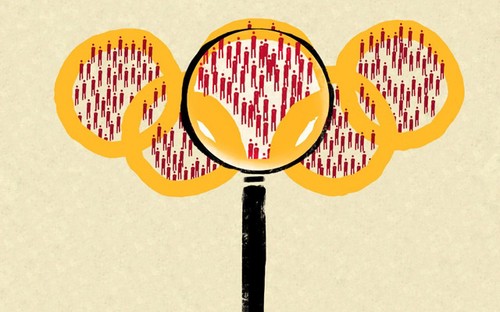

The plan, as the US Olympic Committee vows to throw open the curtains and let in the light, is to get all the names, from all the years and all the Olympic sports, in one place so that people can easily check them before joining a team or hiring a coach or a trainer.

“What we want is an environment where, across the entire Olympic and Paralympic family, the names of individuals who have been banned are readily available,” said Rick Adams, the US Olympic Committee executive who oversees the effort to create a central clearinghouse, under what is called the SafeSport initiative.

The Olympic committee created the US Centre for SafeSport, which it spun off as a separate entity in March 2017. The idea was to have a single agency empowered to investigate and rule on accusations of misconduct, taking those responsibilities away from the organisations that run individual sports, like USA Gymnastics, USA Swimming (caught up in a scandal of its own) and others.

SafeSport does not publish a list of all people barred from the sports, but it does provide links to the individual federations’ lists on its site and it maintains a searchable online database for all the cases in which SafeSport has handed down bans or suspensions — sometimes interim, as investigations continue. From its inception last year through the end of August, SafeSport handled 1,368 reports of sexual misconduct across nearly every sport, the organisation said, with 800 of those cases still open. SafeSport has meted out 149 lifetime bans so far, the organisation said.

(Signs of its early influence, and the broader cultural shift toward reporting sex crimes, can be seen within some of the lists provided by various sports’ governing bodies. Before SafeSport, USA Track and Field had one person on its banned list. Now it has 47.)

When taken together, the continually updated lists of barred people, which include more than 220 lifetime bans for sexual misconduct or abuse in the past 17 months alone, ensure that the frequency of child predation in youth sports in the United States is more fully exposed.

“This goes a whole lot deeper than stopping someone like Larry,” said Rachael Denhollander, a lawyer and former gymnast who was the first to go public with accusations against Nassar. “The number of coaches who are predators on the banned lists is quite huge. The number that are not on these banned lists is, quite possibly, even larger.”

SafeSport received the backing of federal legislation earlier this year. It has an office in Denver, a growing crew of investigators and one set of policies and procedures for jurisprudence. (What it does not have, critics like Denhollander say, is the necessary funding or the independence from the USOC and sports organizations whose years of oversight fuelled the crisis in the first place.)

The effort to more rigorously compile the names is proving to be a delicate and difficult goal. There are about 50 groups that govern individual sports under the Olympic and Paralympic umbrella, some with painfully chequered pasts when it comes to handling accusations of sexual misconduct. Not all have these lists or want to share them.

For now, SafeSport’s public database does not include all the people, however many of them there are, who were barred before it came into existence March 2017. SafeSport left it up to the governing bodies to make those names public.

Before SafeSport, each sport’s governing group handled its own investigations and doled out its own discipline. Handling abuse claims could be unwieldy, expensive and uncomfortable. Revealing them could create public-relations nightmares, which could affect everything from sponsorships to medal counts.

The structure fostered environments of secrecy and unexamined allegations. Part of the concern was legal exposure.

Nudged by Congressional hearings in the wake of the Nassar case, Susanne Lyons, acting chief executive officer of the USOC (she has since been named chairwoman), sent a letter to all national governing bodies on May 31. She instructed each organisation to provide detailed information on accusations, investigations and suspensions or bans that predated SafeSport’s launch. SafeSport hopes to make that information available publicly by the end of the first quarter of 2019.

Shellie Pfohl, president and chief executive of SafeSport, said the mission represented a logistical challenge: creating a database that links 49 national governing groups so they can share information, while also giving the public access to all the names and at least some of that information, too.

SafeSport has no reluctance in publishing names of people it has investigated and barred. What about those barred previously, some many years ago, by one of the national governing bodies?

“We can’t speak to how a case was investigated, how it was adjudicated and the like,” Pfohl said. “That’s why we’re not simply incorporating all the banned lists into our searchable database, into one database.”

Legal experts said that SafeSport and the USOC have the right to publish the information from the sports governing bodies, if it is true and accurate. Claims of defamation would have to prove that the information is intentionally false. Arguments about the lists being an invasion of privacy would be hard to win, lawyers said, unless there was some prior agreement to keep names secret, such as a settlement.

“By further pushing this information out, they’re somewhat vouching for its accuracy and thoroughness,” said Donald Lewis, a lawyer with experience in sexual misconduct cases. “That could create potential problems.”

SafeSport has no interest in re-litigating prior cases, officials said, but it may need to examine them. Jodi Balsam, a law professor at Brooklyn Law School who teaches sports law there and at New York University, said SafeSport might consider informing people that their names will be a part of the public database and offering them a window of time to present reasons they should not be included.

“But you can’t be immobilised by those litigation risks,” Balsam said. “There is good to be done here with the publication of this information. It should be done responsibly, in a way that is not only legal but ethical.”

For now, SafeSport’s database reveals little even about the cases it has investigated since 2017 — only a name, the sport, the decision date, a couple of words to categorise the violation (“sexual misconduct”) and the person’s status, such as “suspended” or “permanently ineligible.”

The pre-2017 reports from sports organisations are far more varied — everything from just a list of names to detailed descriptions of the cases, as is the case with US Figure Skating, which has posted its list online for years.

“The information is useless if it stays internal,” said Patricia St Peter, a past president of the skating organisation. “The purpose is protection — to make sure that this doesn’t happen again somewhere else.”

Other governing bodies, like USA Hockey and the US Ski and Snowboard Association, have not made their lists public, trusting that internal mechanisms and background checks keep the organisations from inadvertently employing those with troublesome pasts.

There remain some sports organisations with no lists at all because they have no barred members. Others are shrouded in cryptic language or blank spaces.

USA Volleyball’s “Suspended Membership List,” for example, contains 53 people, including more than 20 barred in the past year by SafeSport. Of the others, dating as far back as 2002, it can be hard to discern what the infraction was. Many simply say a person was suspended for a violation of the organisation’s code of conduct. Others are blank.

USA Field Hockey has four people on its barred list, but only their names. USA Diving has eight barred members listed, most accompanied by a list of code numbers and letters referencing the violation. The relevant bylaws, when searched separately, are vague enough that one person listed was either involved in sexual misconduct or drug use, or both.

Of the 163 people barred or permanently suspended by USA Swimming, at least 100 were banished explicitly for sexual misconduct (including about 18 by SafeSport.) About 25 others were punished for felonies related either to sexual misconduct or drugs; the information does not delineate. Most of the rest do not contain information to explain why the people were barred.

USA Gymnastics may have the longest barred list. But none of the names have dates associated with their bans, and about half have no violation listed. But 44 reference SafeSport, which means that they were sexual misconduct cases since 2017. Nearly 50 others violated an unexplained bylaw that, when found elsewhere, covers those on sex-offender lists or people who have been deemed to have committed sexual misconduct or sexual abuse violations.

Nassar’s name is on both the list at USA Gymnastics and in the database for SafeSport. In neither place is there an explanation of what actions led Nassar to be barred — nothing about the hundreds of women who accused him of sexual abuse at his sentencing or the conviction and prison sentence he received amid a maelstrom of attention this year.

At USA Gymnastics, all it says is that Nassar violated something called Bylaw 9.2 (a) (iii). You have to look it up to see that it pertains to sexual misconduct and child abuse.

At SafeSport, his entry merely reads, “Sexual misconduct — involving a minor.”

© 2018 New York Times News Service

Comments